THE LATE MR W.G.GIBSON

Mr WILLIAM GEORGE GIBSON, a Dumfriesian well known in connection with scientific and antiquarian pursuits, and for his activity in seeking to popularise various branches of knowledge, died on Monday morning at two o'clock, in the Royal Infirmary. He had been a patient there only for a few weeks; but during a period of eight or nine months he had suffered acutely from a disease affecting the spine.

Mr Gibson belonged to an old Dumfries family, several members of which held the position of Deacon of the Fleshers in the palmy days of the Incorporated Trades. The last of his progenitors to occupy that honourable post was his great-grandfather, Mr William Gibson, who died in 1802. His grandfather, Mr John Gibson, preferred a rural occupation, became tenant of Braehead, in the parish of Kirkmahoe, and was one of the leading farmers of the district. One of his sons, John Erskine Gibson, studied for the medical profession, which he practised with distinction in the town of Dumfries. He died in January, 1833, at the early age of 31 — predeceasing his father by three years and a half — but his life was a busy as well as a brief one. In addition to his professional work, he found time to pen some sketches of an entertaining character for the Dumfries Magazine, as well as to publish a useful pamphlet entitled "A Medical Sketch of Dumfriesshire," and he accompanied Captain Scoresby on an Arctic expedition in which his knowledge of natural history rendered him a serviceable ally.

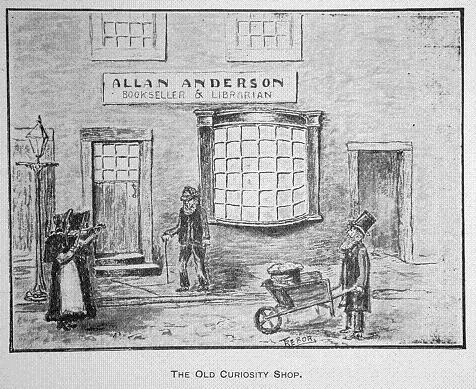

Dr Gibson married Sarah M'Kenzie Rankine, eldest daughter of the late Bailie Adam Rankine, one of the most prominent municipal personalities of his day. The subject of our notice was the second son of this marriage, and was born in 1838; so that he had attained his sixty-second year. Deprived of his father while he was still a child, he was brought up in Kirkmahoe, in the farms of South Duncow and Milnhead, which were successively occupied by his widowed mother, who contracted a second marriage with the late Mr Kirkpatrick. It was intended, we believe, that he should follow his father's profession; but he did not complete his medical course. For some time he was engaged in the business of a book-seller, as assistant to the late Mr Allan Anderson. Subsequently he became tenant of the old Turk's Head Inn, in Irish Street, but it is not surprising that the understanding did not prosper in his hands. He found congenial employment as the secretary of Dr Gilchrist, medical superintendent of the Crichton Institution. The latter was glad to avail himself of the assistance of a gentleman of kindred tastes; and the arrangement afforded Mr Gibson coveted leisure for their gratification. After the retirement of Dr Gilchrist, Mr Gibson left the institution, and until a short time ago he kept at Clerkhill Cottage a private home for patients afflicted with mental disease. He was never married.

Mr Gibson was, along with Dr Gilchrist, one of the founders of the Natural History and Antiquarian Society; and, while never an obtrusive, he continued to be a zealous and useful member. The Mechanics Institute owed still more to his public spirit. He was one of the most active promoters of the successful exhibition held in 1865, to which he acted, jointly with the late Provost Harkness, in the capacity of secretary. In consideration of his valuable services at that time he was elected a life member. And he was equally zealous in his efforts on behalf of the exhibition held in 1873. Mr Gibson had an extensive acquaintance with natural history in all its branches. The science of geology had a special attraction to him; and he was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society several years ago, attention having been called to his work in this field by a report on the strata which were exposed by excavations at the Dumfries Gasworks. Magnetism and electricity also engaged his attention, and he turned his knowledge to practical purpose by the use of magnetism as a curative agency. He was the means of directing attention to a number of antiquarian relics in the district, and was indefatigable in his efforts to secure their preservation. Photography he practised until he acquired the dexterity of a professional artist; and the public are familiar with examples of his art in the form of portrait groups of Dumfries people and of departed local celebrities. Withal, Mr Gibson was a man of social instincts. He took special pleasure in the music of the violin, and sought to encourage its practice among young men, of whom a large number were always included in the circle of his acquaintance, and to whom he was ever pleased to impart his stores of information.

The remains of the deceased are to be interred tomorrow in St Mary's Churchyard.

Extracted from Dumfries & Galloway Standard, 25th June 1890, page 4.

Extract from the 'Ornithologists of Dumfriesshire'

in Hugh S. Gladstone's The Birds of Dumfriesshire — Witherby & Co., London, 1910.

p. xxix GIBSON, WILLIAM GEORGE- , b. at Dumfries, December 1828. Son of Dr John Erskine Gibson, who was surgeon to at least one of William Scoresby's Arctic Expeditions, and died January, 1833, at Milnhead (Kirkmahoe). William George Gibson was a collector of antiquities, and at one time secretary to Dr J Gilchrist, of the Crichton Royal Institution, Dumfries. Appointed first treasurer of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society at the Society's initiation on November 20th, 1862. A correspondent of A G Moore ('Distribution of Birds in Great Britain during the Nesting Season.'Ibis, 1865, pp. 119-142 and 425–458). A contributor to Notes for Naturalists, and The Naturalist. To him we owe the first record of the Blue-winged Teal in Europe (Naturalist, 1858, vol. viii., p. 168). He died 1890.

An interesting account of W.G. Gibson is provided by an article by A.J. Armstrong, which appeared in the Gallovidian, Vol. 3, No. 11, Autumn 1901.

A Dumfries Curiosity Shop

by A.J. Armstrong

It is nigh forty years since I stood one copper-coloured July afternoon by the big bow-window of a bookseller's shop in the High Street of Dumfries, a slim strip of a lad, whose best paid labour had never brought more than half-a-crown a week. I stood there by the big-bellied window reading the titles on the faded covers of the penny song-books and popular reciters, and my gaze even penetrated to the shelves at the back part of the shop to the dust-covered and calf-bound tomes that furnished them.

What a treasure was there, or might be there, and I thought of the Arabian Nights, of The Border Tales, The Black Monk, and The Brownie of Bodsbeck. It was a hard struggle, with a backward, timid nature, ere I could brace my nerves to enter the shop, for a companion had told me that a "boy" was wanted in that establishment to take the blame of keeping things clean, and making a loud noise if any one attempted to decamp with the stock, which stock presented itself to my opening mind as not very fresh and certainly by no means heavy. I stood upon the step irresolute, for I could see no one in the shop, either through the window or between the copy-books suspended on strings stretching from side to side of the glass upper portion of the closed door. After several vain attempts to do so, I at length, and almost noiselessly, entered the shop to find a general air of Bohemian disorder, which told as plainly as tongues that here there was no trade likely to lay the foundations of anything like a colossal fortune.

There was no one in the front shop, so I decided that the glass door with the green moreen curtain must open upon rear premises, where the proprietor of the place was, no doubt, diligently attending to some branch of his business I had raised my clenched fist for an unsteady blow at the counter, to indicate to any or all whom it might concern that I was — though a trifle limp-prepared to discharge the multifarious duties that might be demanded of me. My hand had not reached the board, when my ears were greeted by a man’s voice. "One, two, three," and the sound of a foot laid heavily upon the floor, then a chord of music, followed by a clean, strong, and brilliant dash into a Scotch reel. I had, metaphorically, to chain my feet to the floor, and fix my sense within legitimate bounds, as I listened to the vim and swing of reel and strathspey, and many a time in the after years, when lonely and among the "fremit," I fancied I heard those strains in the old curiosity shop of my boyhood’s time, and my soul yearned for the bluebell and the heather.

The music ceased, and I knocked upon the counter. My heart beat hard, for the voices in the back room were merry voices and not a few. My knock had not been heard; for the mirth and the twanging of strings had drowned it, and almost ere I knew I was again whirled into joyful oblivion to anything but reels and strathspeys, and despite the closed doors the harmony had found its way to the street, until many faces were flattening noses against the panes of the windows and the door. I felt as I could "hooch" to the top of my power, and be justified in doing a "shantrum" of my own.

Of course I had to wait until the music ceased, and then I ventured another blow at the counter. I was heard this time, for a firm footstep crossed the back room floor, followed by a wrench at the door knob which thrilled me to the marrow, and a gleam of the glass panes that almost took my sight away. A portly and withal kindly-faced man stepped behind the counter, and, said he, as he thrust his fiddle under his arm, "Well?"

I stammered out more or less incoherently that, if he wanted a boy to look after the shop, I was his man.

He measured me with the standard of his eye, which seemed to be taking at the same time the dimensions of my moral character, then he glanced round the shop with a smile upon his face, and said in a tone of evident satisfaction: "The shop’s no’ mine, but there’s twae-three things lyin’ aboot belangin’ to me. Ye can come an’ look after them. The place looks lonely wi’ naebody in’t. Ye can whistle on me if onybody rins away wi’ the shop."

While he spoke he kept he spoke he kept twanging the strings of his violin, while those in the rear premises were no less given to twanging. Amid the din I was engaged, and remember my instructions were to "come to Wully Broon’s. Ye ken Wully Broon’s, abune Shaw’s sweetie shop and Dunbar the baker’s? Ye ken the road in; it’s in the Twae Closes? I’ll tell ye in the mornin’ what ye’ll hae to dae."

The morning came, and with it I presented myself at 8 AM. at Wully Broon’s, and was ushered into Mr Gibson’s bedchamber, to find its occupant seated upright in bed, while the gleam of his eye has since and oft haunted me in my dreams by night and day, for there was mirth in it of a variety I noted little of indeed as he instructed me regarding my opening duties for the day.

I took down the shutters and placed them away in the second and windowless back shop; for of back shops there were three, and the third one had a window into the historic Twae Closes. While I was groping in the darkness for the door of this room, which was a step higher than the one I stood in, I thought of the merry twinkle in Mr Gibson’s eye, and so threw myself mentally around to divine the purport or cause of it, when my hand came in contact with the remains of a latch, and with that hand I pushed the door open, and it is only truth to say that I trembled from crown to toe when I entered what seemed to be a place of the dead—a veritable charnel-house, a chamber of horrors of the superlative degree. I hurried towards the window to undo the fastening. Rays of light pointed like misty silver rods to a long row of human skulls ranged upon a shelf on a level and angle with the holes in the window shutter. How I undid the fastenings I cannot tell, but when I turned with unsteady step to seek the sunlight, a human skeleton loomed out of the darkness against the door lintel, as if this "rickle o’ banes" had risen from the depths to bar my passage to the outer world. A dash of desperation and I was past the skeleton, through the row of shops, and I took the proverbial shop-boy’s time to remove the shutter from the window of what I have since designated "Wully Gibson’s bane shop."

About ten o’clock W.G. arrived at his place of business, and the sun of good-natured fun lit up every feature of his face. Of course, I replied in the affirmative to his question if I had got the shutters off, and then he asked me to bring him a jugful of water from the spiggot in the furthest of the room . This I did with the composure of one to the manner both bred and born. He gazed at me intently as he took the jug from my hand, and I noticed the smile was not so soulful as it was when he entered the shop, and when he had paid the "bane house" a visit, it had gone altogether. The fear that had erstwhile opened my eyes and lit them with madness had died out; for I had done good copyhead lines in my time, and I can testify that "familiarity breeds contempt," and so before my master turned up for the day. I had forced myself with a determination worthy of the greatest of causes to familiarise myself with those grinning, gleaming ossifications to such an extent that I had handled them all, even to decorating with an old pirnie the shining dome of his complete boneship.

I became in a few weeks familiar with every object of interest in the old curiosity shop, and I followed with the keenest zest the (at that time) wonderful electrical experiments of W.G. and his friend John Holmes of Brampton, and I can assure the reader that I was frequently, not to say severely, shocked by these experiments.

Almost every morning about eleven came the tall form and kindly face of Thomas Aird, editor of the Herald, and his quiet yet warm greeting to the "boy" has followed that callant all through his manhood and many years of a chequered life. Good, kind-hearted, clever, and sometimes brilliant, my memory carries vividly the cracks he loved and seemed to enjoy. Bird life was to him all absorbent, and the tale is told that birds, wild birds, have followed him from tree to tree, from Mountainhall to the town. One day he came, and with him a stranger, a powerful, strong-faced man, with a far-away look in his eyes. Yet, a light was there that seemed to me so human, aye even verging on the divine. This man was the author of "Sartor," on the shady side of sixty. Yet, what a power there seemed in those rugged features and shaggy brows—a power for the generations when men will read and think. This man was Thomas Carlyle, and when Aird and he left the shop after a long talk with W.G. about Delta (David Moir), an old friend and bosom cronie of Aird’s, I felt that the power of a great spirit had left a glamour over me to last, yea verily, for the long years of a life.

Then came Dr Grierson, of Thornhill, the enthusiastic antiquary and naturalist, and a quaint figure he was, too, as he sat by the ingle cheek in the back shop, "luntin" his short, black clay "cutty," while his thick brown locks hung over his shoulders with such a wealth as would have made many a woman’s pride. Many were the inspiring "cracks" of Roman remains.

"Auld rusty airn caps an’ jinglin’ jackets."

Of hoary fane and ruin grey,

Where grey owls blink

At dawn of day.Dr Gilchrist, of the Crichton, was there too, with the long-locked medico from Thornhill, and he told the Earth’s story with stones, and a grand story he had to tell to a keen sense and a listening ear. I learned to love this modest, clever gentleman, whose amiable qualities went to the heart, and found an ahiding place there.

The Atlantic cable had been laid by Captain James Anderson, and forty years ago a finer specimen of the British sailor could not be found. Sir James came with his experiences and chunks of cable for the old curiosity shop, and many were the pleasant and profitable hours, and welcome the goodly and genial presence of the man.

William M‘Dowall, of the Standard, and M‘Diarmid, of the Courier, were frequent and welcome visitors, for I learnt to feel as if my life needed them, and when the time came that they passed out of it, the heart seemed so lonely, and the years had no yield at all.

There were strange and eccentric characters found their way into this old shop, and a regular visitor was Jean Brand, the old blind fiddler, who together with her constant attendant, Biddy, showered blessings on W.G., for he always remunerated her highly for samples of her musical ability. One morning Jean and her henchwoman presented themselves in front of the shop, while Mr Gibson was having a merry time of it with James Rae, the photographer.

"Man, Rae," exclaimed the antiquary, "What do ye say to takin’ Jean? she wad pay."

Rae grasped the situation as good and favourable, and Jean and Biddy were in due course "taken." The photos sold like cakes, and as W.G. said, it paid munificently. Jean had a unique bowhand and her bowing was all her own. I cannot remember her favourite airs but somehow they were all the same—a selection or fantasia treated as freely as artistic instinct alone could treat. Jean and Biddy were usually attired in huge tartan cloaks of a decided Hibernian cut, and Jean’s sharp variobe scarred features were nearly hidden in the depths of an alpaca coal-skuttle bonnet.

The next character to come under the lens was a frequent visitor and interesting personality, the late John Brodie, whose residence in Townhead Street has recently been wiped out to make room for the newer state of things. Jock, as he was usually named, was a tall man, slightly bent. A shrewd individual he was, too, as his features testified; and as the bargain with Rae, the photographer, abundantly and conclusively proved, Jean Brand and Biddy had been fee’d with a shilling each for "sitting" or more properly speaking, standing in anything but an artistic pose. Jock Brodie knew that Jean’s portrait had gone well, and that his would go well too he was convinced, and so the bargain was struck to Jock‘s material and moral advantage: for had he not been satisfied there might have been in use a strong and strange vocubulary which Jock alone knew the power of. Jock had been errand lad to Robert Burns, i.e., he had run an errand for Jean and had been rewarded with a barley scone and a slice from an ancient kebbuk. But he knew "Rab" and was proud of his knowledge, for he was forceful and keen-sighted and he knew well the value of his information. Jock had had a great career, and many are the good stories told of him, ostensibly, those in his contact with the late Robert Paterson of Nunfield. His was a conspicuous figure at all times as leaning on a stout stick attired in rough frieze trousers, and sleeved waistcoat, he might have been seen seated at his own door any day, greeting cheerily and familiarly all and sundry who passed his way. Blunt and strightforward to a degree, he was greeted in turn by all, and, "Hoo’re ye the day, Scott?" was said to be the manner in which he saluted the late Duke of Buccleuch.

Yet another sitter was obtained in the person of Jamie Taylor, a "taffie" man, whose originality was less conspicuous than striking. Jamie came often for W.G.’s cast-off churchwardens; for he evidently had a predilection for long clay pipes, as those who can remember him will not forget his slow march, with prodigiously booted feet, to the Relief Kirk in Queensberry Street, "tuivin" away at about a foot of clay. Jamie’s great ambition was to stand at the "plate" on Sunday and he remained for long firm in the belief that W.G. would use his influence to that end with the late Rev. John Torrance. Tales, weird, wanton, and otherwise, have been told of Jamie and the Relief "plate, but strange tales are not all truth, and truth is not always strange. He was a "taffie" man of the "taffie" men, and formed a formidable rival to Jock Crosbie, who eventually retired from the confectionery trade to ring the town crier’s bell, and make official and commercial intimations to the leiges. "Taffie" Jock, as Crosbie was called, had for years confined his "cry" to "saut an' whitenin'," but Jamie, more imaginative and resourceful, broke away with several taking rhymes, among them—

Rive an' tear,

The ragman's here."And referring to his candy(?) he intimated, tunefully of course, that—

It’s guid for the young,

As weel as the aul'

It's guid for a hoast,

An' it's guid for the caul'."It might be, to those with sufficient temerity to sample it, I cannot be taken in evidence.

Few will remember "Major Bluebags," but he came too, a curious human shape to an old curio shop. The "Major," Halliday, I believe, was his name, was a monument ranger of a higher type than some whose work was "fitful and in description varied." His form was loose, and loosely and poorly clad, but his face was like a cleanly cut cameo, and his hyperion locks fell upon his shoulders with a classic grace. He delighted in political discussions, and his frequent use of "jawbreakers" did, in no small measure, amuse the habitues of the monument. The "Major" always talked to W.G. in a patronising style, and it was evident he had a decided, if not accurate, sense of his own superiority.

Strange men and strange things are good as companions, and their infiuences are not to be considered unproductive, and I have found that my brief sojourn in the old curiosity shop has been an education I would not have obtained elsewhere. Stuffing huge conger eels, polishing specimen tablets of marble, preserving and fixing star-fish to paper-covered box lids, assisting at the construction of electrical machines, experimenting with galvanic batteries, and a long list of other employments which made up life as "boy" to an antiquary, musician, naturalist: and anything but a money-making man.

Mr Gibson was a man of large heart and keen sympathies, and to him was mainly due the successful concert in the Mechanics’ Hall in 1862 for the benefit of the starving Lancashire weavers. In this year was held the Jubilee of the Dumfries Horticultural Society, and many were the plans formulated in the curio shop for the successful carrying out of the show in the Crichton Asylum grounds. Subsequently, I believe, Mr Gibson was largely instrumental in promoting the successful exhibition to clear the debt from the Mechanics' Hall. Music, science, art, literature, all from time to time found representatives in this old shop, and with Carlyle, Aird, M'Dowall, and David Hogg, the minister of Kirkmahoe, and author of Allan Cunningham's biography, literature had a large share of the company. Archaeology brought Grierson, Gilchrist, Thomas M'lllwraith, the journalist; M'Donald of Hutton Hall, and a host of others. Art knew good, kindly John Ferguson, the Faeds, and the Alexanders. But the music! ah, my heart! there were the reels and strathspeys. The fiddlers keen, alert, enthusiastic, and

"How their ebbucks jinked and diddled,"

as M'Ketterick led and Tibbets followed, while W.G. drove his bow with vim across the cello strings, and burly Tam and Jamie Bell, the Kirkmahoe dykers, made the very rafters ring.

Dear heart! where are they all now? Gone; but not as the days and the years that knew them, for they still find an abiding place in the hearts that lived with them and loved them.

Footnote on A.J. Armstrong

"Andrew J Armstrong was born at Paradise, about two and a half miles south of Dumfries, on the 13th August 1848. Six weeks before this event his father had died of yellow fever off the coast of New Guinea, leaving his mother to face the world with five young children. The family removed to town, and lived for many years in the Kirkgate ... Like most fatherless families, the boys and girls had to go forth and face the world at an earlier age than is conducive to a complete scholastic curriculum; so, after two years' "schuleing" in the Mill-Hole School, Anderson was engaged at the age of nine years to Mr Robert Carswell, grocer, High Street ... At the age of twelve he returned to school, under the tuition of Mr John Menzies, Emeritus Teacher, late of Hardgate, Urr; but through need of bread for the body being more urgent than food for the mind, Andrew was soon behind the counter of the late W G Gibson, bookseller, High Street. Mr Gibson was an antiquary of note in those days and our poet here met and spoke to Thomas Carlyle, in company with the lateThomas Aird, poet and editor of the Dumfries Courier, who by the way printed 'Aja's' first attempt at versification."

The above extracts are taken from 'The Poets of Galfresia' series, which appeared in the Gallovidian — No. VI of the series (Vol II, Summer 1900, pp. 73–77.) dealt exclusively with Andrew J. Armstrong.