Sir William Jardine, our first president, held office from the inception of the Society in October 1862 until the time of his death on 21st November 1874. As his death occured at a time when the society was only having very irregular meetings and there were no printed Transactions the opportunity has been taken to reproduce his obituary notice from the 1873-75 volume of the Proceedings of the Berwickshire Naturalists' Club - a society of which he was also a president. Included with the obituary is an interesting account of a visit to Jardine Hall by a Dr Johnston - it describes the house and estate, excursions to Lochmaben, Spedlins Tower, Torthorwald, Dumfries, New Abbey, Kirkbean, the Colvend Shore at Douglas Hall, Dalbeattie, Munches House, Dumfries for a second time to include Burns' House and Mausoleum and Applegarth Church.

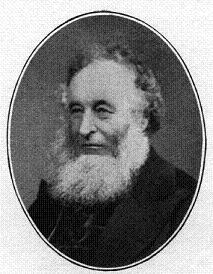

Obituary Notice of Sir William Jardine, Bart., of Applegirth

Sir William Jardine, Bart., the eminent naturalist and ornithologist, was born at Edinburgh, 1800. He was educated at home to the age of fifteen, and then at York where, as he often related in after life, he was “sent to learn English.” From York he went to Edinburgh, where he studied Medicine and Anatomy; and his scientific training at the University of Edinburgh, laid the foundation of that love for Natural History, which so distinguished him in after life. Here he attended the lectures and geological excursions of Professor Jameson, and the botanical lectures of Mr. James Scott; while his studies in comparative anatomy, were carried on under Professor John Lizars, who afterwards became his brother-in-law, as he afterwards married his sister in 1820. He then pursued his anatomical studies in Paris; but his father, Sir Alexander, dying in 1821, he returned to Scotland to fulfill the important duties of a large landed proprietor.

At all times he was a keen sportsman, both with rod and gun, and when a young man was a hard rider to hounds. More than once he has been known to dash into the flooded Annan on his favourite horse, when fox and hounds had crossed the water, which to others was dangerous in the extreme, as the stream is very rapid when in flood.

In 1825, he published jointly with Mr. P. J. Selby of Twizel, “Illustrations of Ornithology ;“ the 4th volume of which was not completed until 1843.

In 1831, was founded the Berwickshire Naturalists’ Club, the first established of the many Field Clubs now in existence throughout Great Britain; Sir William Jardine was elected a member in 1832, and was President in 1836.

In 1833, he commenced the editorship of The Naturalists’ Library, in 40 vols.; which occupied him for 10 years, many of the volumes being written by himself. In 1831, he assisted in conducting the third volume of the Edinburgh Journal of Natural and Geographical Science. He was also in 1837-8, joint editor with Dr. Johnston of Berwick, and P. J. Selby, of the Magazine of Zoology and Botany; which after the publication of the 2nd volume merged into the Annals of Natural History. He was also joint editor - with Dr. Balfour and others, of tbe third series of the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal.

In 1834, he went on a tour through Sutherlandshire, in those days, as far as Natural Science went, an unexplored country. He was accompanied by his youngest brother, John Jardine, Mr. Selby, and Mr. James Wilson; and the naturalists were provided with every appliance for the collection of plants, birds, and fishes. Their conveyance was a boat upon wheels, drawn by two Highland ponies; and this served them well for fishing the lochs, and for visiting the haunts of wild fowl and other rare birds, which sought the unfrequented moors and waters of Sutherland. The boat often served as a sleeping place, and many nights were passed under-neath its shelter when turned over as a covering from the weather. It was during this tour that the great lake trout, Salmo ferox, was discovered and described; while the study of Icthyology was henceforwards added to the other studies of this accurate observer of Nature, and led, eventually, to the publication of his beautiful work on British Salmonidae. Previous to the publication of this work, Sir William had undertaken numerous experiments on the rearing of young salmon and trout, in a small pond prepared for the purpose; and these were from time to time turned into the Annan, marked by small rings, or other devices, which led to several being recognised, and their weight registered, when taken months afterwards. He often visited, and gave the benefit of his advice, in the establishment of the Stormontfield Ponds, which were under the care of Sir John Richardson, Bart., of Pitfour. Indeed, his knowledge of Icthyology led to his appointment in 1860, as the principal Commissioner appointed to investigate the Salmon Fisheries of Great Britain, and the causes of their decay.

Another study, by which Sir W. Jardine became known to the scientific world, was that of Ichnology, or the study of the footprints of different animals, when left imprinted upon the shores of seas, lakes, or rivers. He was induced to take up these investigations, from the fact that numerous footsteps of extinct reptilian animals were found on the Jardine Hall property, at the celebrated Corncockle Muir Quarry, in the Permian sandstones of Annandale. This led to the publication in 1851, of the valuable Monograph, known as the Ichnology of Annandale.

In 1844, the Ray Society was established. It was proposed almost simultaneously by Dr. Johnston and Mr. Hugh E.Strickland, the son-in-law of Sir William. In answer to a letter on this subject from Mr. Strickland, in Dec., 1843, he wrote,— "In regard to the Ray Club, it is one of those things which if established with sufficient funds to publish 2 or 4 vols. annually, would do much good; and it is one of those things which may hang on for ten years by talking; meanwhile, if you approve of the general plan, get as many subscribers as possible." Details of the establishment of the Ray Society are given in the “Memoirs of H. E. Strickland,” p. ccxiii, to p. ccxxvii.

Ornithology was nevertheless the study which Sir William followed with untiring perseverance; and his ornithological museum at Jardine Hall, was probably unrivalled by any private collection in Great Britain. Prince Bonaparte, Jerdon, Blyth, Hodgson, Gosse, Kirk, Gould, contributed from time to time to the collection of birds, which were accumulated from every quarter of the globe, and of which, at the time of his death, he had all but completed a detailed catalogue; marking each variety of plumage, age, and sex, with the localities where each bird was found, and the person from whom the specimen was obtained. The stuffed British birds, in the museum, were chiefly shot and preserved by himself. Some of these are now extremely rare, and difficult to obtain.

In 1848, he commenced the Contributions to Ornithology, which were continued until 1853, when the work was given up, chiefly owing to the shock caused by the death of his distinguished son-in-law, Hugh E. Strickland. In 1855, he published the 1st vol. of Ornithological Synonyms; and in 1858, the Memoirs of Hugh E. Strickland; which, with the exception of some contributions to the New Edinburgh Philosophical Journal, were the last emanations of his pen.

He was president, from its foundation, of the [Dumfriesshire and] Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, and a contributor to the papers of its Transactions. Indeed, he was the Laird of Spedlins Castle; that old border baronial tower of the Jardines, by 'the Annan water wan ;' of which Grose tells the strange story of the ghost of a starved man, by which it was haunted. There are few Ornithologists of modern repute, who do not owe much to days passed at Jardine Hall, and to lessons in ornithological research, which they learned at the feet of the veteran Naturalist who has passed away; and who will ever be remembered with respect by those who had the privilege of his acquaintance, and with sincere affection by those who loved him as a friend.

Sir William Jardine was— Doctor of Laws and Learning; Fellow Royal Society; Do. Royal Society of Edinburgh; Do. Linnean Society; Do. Physical Society of Edinburgh; Do. Meteorological Society of Scotland; Do. Anthropological Society of London ; Do. Microscopical Society of Edinburgh; Do. Botanical Society of Edinburgh; Do. American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia; Do. Ornithological Society of Germany; Member of the Wernerian Society; Do. Berwickshire Naturalists’ Club; Hon. Member of the Tyneside Naturalists’ Club; Do. Cotswold Club; Do. Malvern Club; Do. Woolhope Club; &c., &c.,

SIR WILLIAM JARDINE

Sir William Jardine died at Sandowne, Isle of Wight, on the 21st November, 1874. He was the sixth baronet of Applegirth. The owner of a fair estate in Dumfriesshire, where he generally resided, he took a leading part in the public business of the county; and he was especially active during the prevalence of the cattle plague there. On one occasion he came forward as conservative candidate for the representation of that county in Parliament, but retired before the day of election. He was appointed a Deputy Lieutenant of Dumfriesshire in 1841.

"In social life," we are told, "Sir William Jardine was most genial; all his weight of learning sat lightly npon him, and the smile which lighted up his face was as sweet as it was frequent."

He may almost be said to have been an original member of our Club, being elected at the first anniversary, Sept. 19th, 1832. He then resided at Holmes on the Tweed, which stands a few miles farther down the river than Melrose. He was the fifth President, his "Address" being delivered at Yetholm, Sept. 21st, 1836. He commenced for the Club a series of papers on the Salmonidae, but only finished two, viz.—

1. Notice of the Herling of the Solway being found in the Tweed, with some observations on its habits and distribution.— Hist. Ber. Nat. Club, vol. i., p. 50.

2. Notice of the Parr. Ibid, p. 82.

A list of his numerous writings, up to 1850, may be found in Agassiz and Strickland’s Bibliographia Zoologiae, vol. iii., pp. 317—319; published by the Ray Society.

As a befitting sequel to this Memoir, the Club is indebted to Mrs. Barwell Carter for the communication of a journal, written by her father, of a visit paid to Jardine Hall, in 1844; recording Dr. Johnston’s impressions of Dumfriesshire and Galloway, and his opinion of Sir William, derived from personal intercourse. It forms a pleasing episode in the lives of both distinguished Naturalists.

AND now we found ourselves in the avenne leading to Jardine Hall, where a most friendly and cordial reception awaited us, and we were soon at comfort and ease with the family.

Tuesday, 10th September. I spent this day in a stroll through the gardens and grounds of Jardine Hall, and through part of the estate. The House, built of a dark red sandstone, reminded me of Twizel House, which it resembles in outward appearance, but the interior arrangements are entirely different. There were many things to interest us in the gardens, which are well kept; and the grounds contain many fine trees, especially beech and ash, and a very large hawthorn stands near the house, which Mr. Selby has engraved in his History of British Forest Trees. Sir William Jardine pointed out to me some beautiful and thriving specimens of the Firs that have been introduced of late years into this country, and which grow here very fast and freely. In my stroll adown the Annan—a sweet stream—I noticed some small shoals of Dace, called here “Skellies,” a fish I had not seen previously; and here too I gathered for the first time, Jasione montana, and was much taken with the beauty of its dark blue flowers. It grows in profusion in all this part of Dumfrieshire, some fields being as full of it nearly, as they are of the daisy with us. Several species of polygonums — Hydropiper, lapathifolium, and .Persicaria —abounded to a most noisome degree in many of the fields; which, indeed, in general seemed almost choked with annual weeds.

The contrast between the land here, and in Berwickshire, is greatly in favour of the latter. The only plant of rarity I gathered was Utricularia intermedia. It grew in abundance in a ditch cut through a swampy field, which not many years ago was a pond of resort for myriads of wild ducks. It is now firm enough to bear a coarse sort of grass, which is annually mown and makes good meadow hay ; and this conversion from water to solid land, is solely the result of nature, and of the annual decay of the aquatic plants that grew in the lake — the pond — the morass—the bog— and which will ere long be the meadow. About Jardine Hall, Lepidium Smithii grows plentifully, and I observed it to be common in other parts of Dumfriesshire and Galloway. Polytrichum urnigerum was most profuse, on banks by the road sides, in our walk this day, and was really an interesting object.

Wednesday, Sept. 11th. Soon after breakfast Sir William’s carriage was at the door to take a willing party to Lochmaben and its Castle. The drive was pretty enough, but chiefly interesting from its novelty. It took us through the royal burgh of Lochmaben, an insignificant town with some antiquarian interest; and a pillar of granite, erected by his nephews to Mr. Jardine, who went from this, his native town, to China, where he prospered and grew rich, and succeeded in making some relatives grateful by his death. One of them, Mr. Johnstone, has his residence close at hand, where he has built a handsome range of stables, and prides himself on being the owner of Charles the 12th. This gentleman who now enacts the squire and the sportsman, had been educated for the profession of a surgeon, and was for some time an assistant in the navy. He dined with us at Jardine Hall yesterday, and was pleasing both in his appearance and manners. Lochmaben is a large sheet of water, for nothing so remarkable, as for containing an abundance of the Vendace; and for being the locality of Bruce’s Castle, which stands on a peninsula that juts out on one side of the lake. This Castle has been a place of great strength and noble architecture; to judge from its crumbling remains, which are now surrounded by many noble ash trees. I brought away with me a memorial or two from the walls of a place which is said to have been the favourite residence of Robert the Bruce.— (Chambers’ "Picture of Scotland," p. 97.) Chambers here confounds Lochmaben Castle with Bruce’s Castle; the latter is the fortress erected by Bruce, the former the old castle which supplied the materials. We botanized an hour or so by the lake, and here I gathered for the first time, in a growing state, Typha angustifolia, Bidens tripartita. et cernua, Sison verticillatum. We also gathered here Cicuta virosa, Radiola millegrana, and Scutellaria galericulata. We walked afterwards to Lochmaben Castle, which is nigh at hand; and the slight remains of which are covered up with a green sward, on which sheep were quietly grazing. We must come to this at last, as well as baronial castles. The view from the Castle’s mound was extensive and fine, but the details of it have already faded from my memory, probably because it was too extensive and indistinct. All I can remember is the lake at its base, and above, the Burgh of Lochmaben, a lake not half the size of the former, but plenished like it with the celebrated Vendace. We were now again joined by the party in the carriage, and drove some miles on a road that carried us homewards; when Sir William, Mr. Macdonald of Rammerscales, and myself alighted for a walk across some extensive muirs that form part of Sir William’s property. It was in this walk that I gathered Ornithopus perpusillus for the first time; and my pleasure was increased manifold, when shortly afterwards I saw growing in its sphagnous bog, the Andromeda polifolia: less heightened certainly by the intrinsic beauty and delicacy of its drooping blossoms, fair though these be, than by the memory of the poetical and beautiful description Linnaeus has given of this daughter of Cepheus, and which now came strong upon me. Oh! when shall we have a flora of Britain embued with the spirit — the love of that master mind! A flora, not on the model of the "Flora Lapponica," but, conceived in its spirit, and executed with its taste and talent, would spread the study of botany far and wide amongst us, and would in itself be a society for the diffusion of entertaining knowledge. And so musing we left our fair flower, and hastened onwards to inspect the Spedlings, the ancient fasthold of the Jardines of Applegirth. This is a very interesting Tower, and entire so far as the outward walls are concerned; for the roof has fallen in, and many of the interior walls are now decayed. The dining room has been a fine room, with a noble fireplace, ornamented with a large marble chimney piece; the room is arched like an oven, and in the recesses through which the light comes, are stone seats for guests. There has been no lack of accommodation for small and retired parties to consult together, even in the common hall., We were shown the entrance to the dungeon, and had again the story of the ghost and the bible. Ascending to the top I plucked a few leaves of ivy, that was doing its best to ornament this deserted residence; and deeply did I sympathise with the owner of it, that it should have been left thus vacant, and exposed to destruction; when it might have been repaired and restored and made habitable, for the sum that was expended in building the modern house, that stands on an inferior site on the opposite side of the Annan. There must have been some great defect of heart — some sad lack of love of ancestral deeds, a no-love of fatherland; that he who first left this place of family pride, should have seen no virtue in its restoration and preservation. I deem him to have wronged the present talented baronet and his descendants for ever. And now we waded the Annan, and so home to dinner; all mourning over the Spedlings. In the evening, we were shown the famous ghost-laying bible, and a very beautiful volume it is, kept in a box formed of a rafter of the Tower. It is in its original binding repaired; and is printed in a beautiful old English letter. Looked over also some proofs of a volume preparing for the Ray Society, and am not pleased with the same. Mr. Macdonald, who translates a considerable portion of the volume, is a country gentleman of property, who lives about six miles from Jardine Hall, in a house famous for the difficulty of access to it; so that visitors often leave their carriages at the base of the hill and ascend on foot. It is not less dangerous to descend this avenue, as witnesses this true story. Mr. Macdonald is the nephew of the late proprietor, and driving his uncle down the road in question, the gig was overturned, the uncle was killed; and Mr. Macdonald found himself the Laird of Rammerscales several years anterior to the laws and ordinations of Nature!

Thursday, Sept. 12th. A long drive to-day. Starting immediately after breakfast, we took the road to Dumfries; which for some miles was very uninteresting, and would have been more so, had I not had Sir William to tell me the names and history of the more prominent objects and hills in our view. These I have now almost forgotten. The first and better half of our road was very much of a continued ascent, until we reached a poor village, with a name so foreign to my ears, that I could not retain it in my memory. There is a considerable seminary, or "Classical and Commercial Academy" in it, but we saw none of the scholars or boarders. From the hill above this village, there opened upon us a fine view, which reminded me of Milfield Plain; but the latter had a decided superiority in all respects. The plain below was a large basin encircled with hills, traversed by the little river Lochar on the nearest side, and occupied by the town of Dumfries to the south-west. Lochar Moss lies in the centre, an enormous peat bog of about 10 miles in length, and 3 in breadth; and our road cuts it into two unequal halves. This road is remarkable for its origin: a stranger, a great number of years ago, sold some goods to certain merchants at Dumfries on credit; he disappeared, and neither he nor his heirs ever claimed the money; the merchants in expectation of the demand, very honestly put out the sum to interest; and after a lapse of more than 40 years, the town of Dumfries obtained a gift of it, and applied the same towards making this useful road. We presume the good folks of Dumfries had concluded that the stranger had laired himself in this bog, and sunk in one of its pits, which served him for an untombstoned grave, a thing they of Dumfries seem to have in fear. Lochar Moss supplies the good people of Dumfries with an abundance of peat, which is the fuel with the commonality all over this district, and there were workers of it scattered throughout the moss. There is a certain interest about these men, who appeared to be of the lowest class in general. No noise attends their monotonous labour, the spade cuts without grating, the clod is thrown aside without evoking a sound, there is no converse, each toils by himself, without giving or receiving another’s orders or directions; silence reigns around, and imparts to the labour a peculiar, but rather disagreeable, interest; for this outward solemnity of nature tells not favourably on the minds of men of the low degree of cultivation these have. Solitude is not for them. Dumfries is a very fine town. We walked through its broad, clean, busy street with pleasure, admired its shops, its bridges, and its magnificent asylum for the insane, at a little distance on a. wooded bank above the Nith; drove through the pretty suburb of Maxwelltown, and following the course of the Nith, took a seaward direction. The road was greatly improved in interest; the land and the style of farming good. We were not long in arriving at New Abbey, where we rested an hour, in order to examine its beautiful remains. Within its walls there lie the bodies of many Maxwells, the prevalent families in this neighbourhood; and as the head of them is a Roman Catholic, there appear to be many of that religion hereabouts. Near the Abbey there is a Chapel and manse for the priest and his charge. Leaving the Abbey, we had a pleasant walk through the churchyard; around the old garden, with its fern-clad wall; and up the road a little, where it is lined with a double row of limes, that meet overhead and form an avenue, where monks may have mused, or conned their sermons, in days of yore. There is a monument in the Abbey, erected to the memory of two young gentlemen — brothers,— who were drowned together hard by; and I now feel sorry that I did not take a copy of the inscription on their tombstone. I gathered some memorials of the place from its damp walls, which the ivy strives in vain to decorate. It is trite to make contrasts, for, in this world everything must suffer change and decay; nor doth it seem of use to revive a picture of the Celebration of High Mass, with all the gorgeous pageantry, in an Abbey that now shelters a herd of cows from the inclemency of the weather. What may be the thoughts of the spirit of the Lady Foundress, I know not! How vain it is to attempt to immortalize our affections, which are, and must be, part of our perishable organization! The Abbey was founded by Devorgilla, daughter of Alan, Lord of Galloway, and wife of John Baliol, Lord of Castle Bernard, who died and was buried here; his lady embalmed his heart and placed it in a case of ivory bound with silver, near the high altar; on which account the Abbey is often called Sweet Heart, and Suavi-cordium.* Again we are on the road, and attention is kept awake by the novelty of every scene and object we pass. But the first place we note is the neat and pretty hamlet of Kirkbean; whose ornate character tells as plainly as a guide could, that a rich proprietor’s residence is at hand; aud a triumphal arch erected across the road proclaimed to us that this proprietor, Mr. Oswald, MP., for Ayrshire, had brought to the favourite residence his lady, the widow of the late Sir James Johnstone of Westerhall, to whom he had been married about three weeks ago. And next we admire a small and humble cottage, covered in front with the vine and fig tree, which appeared to be in a flourishing condition; and I observe that all hereabouts, and afterwards on our route, the brambles abound to a degree greatly beyond what they do on the Eastern Borders, and are loaded with fruit. The species too are not the same as they are with us. The prospect improves as we drive on, and we often stop to admire it; the Solway and its broad sands, the Westmoreland and Cumberland hills, the opposite coast with its indistinctly seen villages, the hills and woods of Gallovay. Many interesting localities were pointed out by Sir William which served the purpose of raising and satisfying a curiosity that died away on the spot. We nighed the shore of the Solway; the road sides rough with brambles, and rich in many other plants that interest an eastern botanist. Sedum telephium, almost unknown on the eastern side of the island, was not uncommon here, truly wild and luxuriant. But it was as interesting to notice the different habit which some plants, common to the two districts, here assumed; in general they were more luxuriant. The banks too, where steep and elevated, were clothed to the very base with a very rash vegetation of numerous plants, and with trees and shrubs. A rock called "Lot’s Wife," at the foot of a rocky deep ravine, was a tempting object, but time could not be spared for a descent upon it; it was rich in many a flower, and at an earlier season must have been gay and joyful with their various blossoms. We halt at Douglas Hall, a hamlet of poor cottages, where it was difficult to find accommodation for the horses. And then we had a nice stroll, first over some links, where I gathered Thalictrum flavum, which is a rare plant in Scotland, and Erythraea linarifolia. Ruppia maritima was plentiful in some pools of brackish water. We then entered on the Solway sands, which spread far and wide, around and before; my head was full of Sir Walter Scott and his vivid descriptions of them. This extent of sands has a grandeur and solemn influence, which is greater than one could imagine mere extent of a fiat surface could give; but you feel the scene, and that feeling would be even oppressive — fearful perhaps — were one alone to traverse their weary and watery level. After walking a short way over this fiat surface, we reached a coast bounded by a rocky precipitous bank of great height and rugged beauty. The rocks were hard and sharp as flint, of a reddish colour, broken into acute angles and masses, and caverned with many caves that lead sometimes far inwards. Often an enormous mass of rock had fallen down and concealed the front of these dark recesses; and more than one might have been the type of the cave that sheltered Dick Hatterig and his ruffian smugglers. As this fine and bold piece of coast was wooded too to the very ledge, there were other places whence Kennedy might have been precipitated ;— indeed the scenery seemed to be exact to that described by Sir Walter Scott, in his "Guy Mannering" It is of these very rocks that Chambers says :— "It has been supposed, with no inconsiderable degree of probability, that they furnished materials for the scenery of Ellangowan."— I enjoyed this scenery greatly, and it was rich also in a botanical view. First in interest, there was the Samphire, growing in places whence to have gathered it would be indeed a "dreadful trade." — "Half-way down hangs one that gathers Samphire,— dreadful trade !" Sir William told me, that within his memory a man living at Douglas Hall, was wont thus annually to collect Samphire from these rocks. I succeeded in reaching one tuft, which supplied me with specimens as memorials of the Colvend rocks; which, I ween, are somewhat grander than those of Dover, and not less immortal in man’s memory were they; in fact, the objects the great Northern Novelist had in his eye, when he drew the coast scenery of "Guy Mannering." The Pyrethrum maritimum grew here abundantly, also in inaccessible spots; but it was truly ornamental, as its large white flowers showed bravely with the dark rock behind, The rock was studded everywhere with these and other sweet flowers. The Arenaria marina, Silene maritima, Statice armeria, Sedum telephium, Cochlearia officinalis, Asplenium marinum, commingled themselves on the rugged front, with wiry grasses, the Ivy, the Holly, the Whin, and several fine arching briars and roses; while on more exposed abutments, several yellow and green lichens found space to spread their circular patches. Sir William pointed out one or two specimens of the Yew, which would seem to be indigenous here. Left this scene with reluctance, and ascending the bank, we returned to Douglas Hall by a high road, that afforded extensive views of the Solway and the coast. I know not in what direction we were now driven; but the road was tortuous and interesting, and fringed on each side with numberless briars, the species different from those of Berwickshire, and more productive of fruit. The hills around us were granite, and the country was very unequal and rocky; so that Galloway must be as ticklish a place as Galway, for the gentlemen who love to follow the hounds fair; indeed we were told that fox hunting was here an unknown sport, and the proprietors give 10s 6d. for every fox that any countryman may destroy, by fair means or foul. There were many valleys stretching up and between these rough hills, that, as a botanist, I yearned to explore; but, it was onwards we must go, contented with the glances of fields which it seemed very certain I would never again re-visit. Oats and barley appeared to be the only corns cultivated, and the fields were redolent of annual weeds. Peat mosses were numerous, and in each of them a solitary individual worked away in cheerless silence. After a long stage in which we had passed very few houses, and not even an onstead, we came to Dalbeattie, a nice looking village that looks as if it had been set down in this thinly peopled district by some mistake, and one wonders what the inhabitants of it can find to do. Yet it has every symptom of comfort about it, and the stone houses are all covered with blue slates, and white washed. There is a good Inn in the village, and a mail coach passes daily through it. A few minutes drive now brought us to Munches, and to the end of our day’s travels.

Friday, Sept. 13th. Munches is the residence of Mr. Maxwell, a young gentleman married only a few months since, to the eldest daughter of Sir William Jardine. The house has nothing notable in it, but the grounds are beautiful, and in the neat flower garden we found a great display of fine flowers, groups of which were likewise tastefully planted about the house. I enjoyed a morning stroll in this pretty garden, and over the grounds very much; and the pleasure was heightened by the company of Mr. Maxwell, who hourly improved upon us. He is really a very excellent and amiable person, very fond of farming, and anxious to adopt modern improvements, which from a deficiency of chemical knowledge, he has a difficulty of explaining or comprehending. I never saw such capital specimens of the Scotch Fir as grow here, and the Beeches too are superlative; all Mr. Maxwell’s woods were indeed thriving. The hills which bound the grounds are clothed with young wood; and as they are granitic, very pretty, and much broken up into scaurs and ravines, they presented a very tempting field to a botanist, which we must leave others to investigate. From the hills about us large quantities of granite are quarried and exported to Liverpool and other places. We were told that some had been sent even to America. Yesterday we had to dinner, and this morning to breakfast, a dish of Spirlings or Smelts; the first occasion on which I had eaten this small but delicate fish. It is taken in abundance in the Urr, a small river, or rather muddy canal, which bounds the grounds of Munches, and up which the tide runs with considerable velocity. The water is turbid and drumlie with a fine mud, that makes a smooth bottom to the water. On its banks the Scirpus maritimus grows in profusion; but to remind me of Munches, I preferred gathering a specimen of the common Polypody from Craig-Turrock, a picturesque rocky mound in front of the house, and very prettily ornamented with various shrubs and flowers. About mid-day left Munches and again passed through Dalbeattie; when we diverged into a new road, which took us straight to Dumfries. The drive was at first not very interesting, and we had few brambles on the road side. After several miles we entered the pass of the Long-wood; a pass between the hills, which gives one a lively idea of the difficulties an army must encounter, in forcing a passage through such a road, defended by troops on the banks on each side, and on the turns in front and behind. The passage is fine and interesting, and the descent very steep on the Dumfries side. Well, we are once more in the beautiful town of Dumfries, and we take a stroll down its quay; and after satisfying our admiration of the views up and down the Nith, we visited the churchyard, remarkable for the great number of its expensive tombstones, engraved with epitaphs of all sorts and sizes. Some of the stones possess considerable interest; such as those which commemorate the deaths of the Scotch Martyrs, and the benefits which the town had derived from the services of a Provost of the time of King James the 6th. But the principal object of interest in the churchyard is the mausoleum of Burns, where his mortal remains lie; and generations yet unborn will visit the spot, led thither by the same feelings that led us,— admiration and gratitude, and love, and pride, and mournful sympathy. I resolve here to re-peruse his everlasting works, and I must some day fulfil my vow. Our curiosity satisfied, we next went to see the house where he lived the latter years of his life, and in which he died. I like the remarks of Chambers on visiting this mausoleum ("Picture of Scotland," p. 104); and am well pleased to have seen it. Guide books now a days make a traveller’s Journal very short; and so without mention of what other things we saw there, we leave the town and return to Jardine Hall by the same road which we travelled yesterday. And our long journey made us enjoy with zest our dinner, to which we had the Vendace; and an epicure may esteem the man fortunate, who could thus have the good fortune to eat, two days in succession, fishes he had not tasted before. The Vendace is a very delicate fish.#

Saturday, Sept. 14th. The rain fell incessantly, and so heavily, that we were confined to the house; and found not an hour of the day in which it was possible to have a stroll. So we occupied ourselves in examining the library; which contains some fine and interesting works. Perhaps none of them interested me so much, as some original letters of Wilson, the American ornithologist, and copies of the only two engravings he ever executed. Sir William Jardine is a sincere and hearty admirer of this wonderful man and naturalist, and there is something in common between them. Sir William is a man of talent, of quick and original observation, and of considerable acquirements; but be wants decision, and has had a defective education. Still, there are few naturalists who are equal to him in mental character, and who study their science with the same high views; which his limited command of language does not allow him to do justice to, or develop in a manner that takes with the public. I like my friend much, and have every reason to be pleased with my visit to him. After the Library we examined the Museum, and his various collections. Perhaps the things that most took my fancy, were two glass beads of the size of marbles, which the common people everywhere call Adder’s Eggs; and which antiquarians seem puzzled to say what they were. That they are of Roman manufacture is undoubted; but for what purpose were they made? The specimens in Sir William’s cabinet were found in a peat moss on his estate; and in the same moss there were found a small brass kettle and pot, which are also in his possession. Pennant delineates a pot exactly similar to the one we were examining. Upon the whole, this was an interesting day; and a pleasing variety to those we had of wandering "here awa, there awa."

Sunday, Sept. 15th. The rain continued to fall without interruption; and the Annan had risen higher than it had done for several years back. Lessening in severity however, we ventured to the Parish Church at Applegirth; which is distant rather more than two miles from Sir William’s residence. The Reverend Dr. Dunbar is a clergyman much above the average of parish ministers in appearance, manners, and talents; and his sermon was composed with care, and delivered with chaste propriety. It was chiefly doctrinal, after the fashion of Presbyterians; and this seemed to me an error, considering that the class to whom it was preached were principally agricultural labourers. From the Manse garden we had an extensive view of the Annan, which had now risen above its banks, and overflowed all the adjacent haughs. Corn fields were flooded, and here and there people were busy removing the crop from amongst the water; while in other places carts were standing axle-tree deep in the water, arrested while the work of removal had been going on. The scene reminded me strongly of a similar one described by Thomson in his "Autumn." —

“And still

“The deluge deepens; till the fields around“

Lie sunk and flatted in the sordid wave;

“Sudden the ditches swell; the meadows swim.

“Red from the hills, innumerable streams

“Tumultuous roar; and high above its banks

“The river lift, before whose rushing tide,

“Herds, flocks, and harvests, cottages aed swains

“Roll mingled down.”

The poet has very probably drawn his picture from scenes which he must have seen when a youth in his native district, exaggerating the details a little after his own way. In the churchyard at Applegirth, there grows a very fine and very large ash tree; from which in the good old times, the Branks were suspended, ready to be used to restore the quietness of the household; when the good wife’s tongue had wagged too freely, and railed too loudly, in the judgment of the Kirk Session. Now wives speak in a softer key, or Kirk Sessions are more tolerant; for the Branks have, from long disuse, become barked over and buried in the tree.

The storm having ceased, and the mist cleared away, we left Jardine Hall at 5 o’clock in the afternoon; not without a feeling of regret; and very grateful for the kind attentions we had received from Sir William and Lady Jardine, and their dear family.

* ["She feundit intil Galoway

Of Cistertians order an Abby,

Dulce Cor she gart thame all

That is Sweet Heart the Abby call,

But now the men of Galloway

Call that Steid New-Abby." WYNTOWN.

It is named by Lesly "Monasterium novum, seu Sauvi-cordium." —De Origine, &c., Scotorum, p. 9.]# Sir William Jardine’s account of this fish may be found, along with a figure, in the Edinburgh Journal of Nat. and Geog. Science, vol. iii., pp 1-5.